Some good news is that they like grain and will come for it.

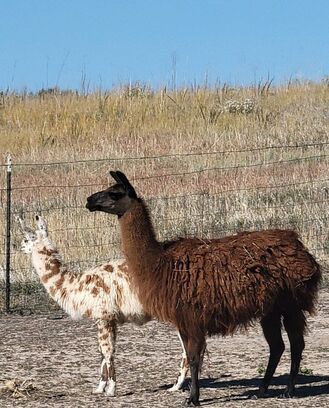

The 4 girls were brought back to Albuquerque where they were penned adjacent to our other females. Little Girl with an injury, her mother was Izzy, Groot, and Duchess were the other two. Groot was the most nervous of the group. Izzy and Little Girl were very compliant.

Jodi and I took turns cleaning her 2x a day and used a solution of weak betadine for flushing and silver antibiotic spray and finished with a gentle fly repellant. We did this for two months.

One day I had a group of veterinary technician students over and their instructor who looked at Little Girl. I pointed out that there was some tissue that looked necrotic to me so I decided to cut some of it off. Little Girl did not even flinch but the snip that I took was like a 1 inch circle and it bled, to my horror.

Little Girl passed away on July 20, 2023. She was active until the morning we found her. Mysteriously, Duchess went down only about a week later. We examined Duchess and discovered she was an intact male and renamed him Duke. Duke ate and drank but would not get up. Duke died July 30, 2023 of unknown causes. Perhaps he was very upset at the loss of Little Girl. This was a very hard summer with these losses. Izzy and Groot were ultimately adopted later in the summer and have a lovely new space in the mountains near Santa Fe, NM.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed